There is plenty of room for honest disagreement on economic policy. Normally, it’s about trade-offs among worthy goals. Having more of one good thing will mean forgoing another good thing. People can come to different judgements about which good thing is best, or most important.

But some policies are, and I’ll be blunt here, stupid. Completely stupid.

Stupidity here doesn’t just mean something Eric doesn’t like, or something economists in general don’t like. A policy is stupid if it is a terrible way of trying to achieve any reasonable objective, if it is incredibly costly relative to other available alternatives, and if it wrecks other important objectives along the way.

Taking GST off food generally, or from fruit and vegetables, is stupid.

Yes, other countries do not impose GST on food or have other exemptions for worthy-sounding goods or services. But those kinds of holes in GST come at substantial cost. They make it harder for the government to raise revenue for the things voters want, while imposing insane administrative costs at the same time.

Let’s start by pretending that the policy is simple to impose and administer. It isn’t. Nobody has been able to make it work well, because the policy is stupid. But let’s pretend for now that all would be simple. We’ll get into the administrative difficulties later.

A tax system has one big job. That job: collecting revenue for the government as efficiently as possible.

It’s a hard job. All politically-possible taxes are at least somewhat distortionary. They cause people to avoid the thing that is taxed, in favour of things that are not taxed. If you tax income, people work less. If you tax consumption, people shift into leisure activities that are not taxed. If you tax income from capital, people invest less. If you tax wealth, wealthy people shift assets or themselves overseas, along with their otherwise-taxable income, while creating less new wealth.

The tax that causes fewest problems is a tax on the value of unimproved land: the underlying value of land before anyone has done any work to improve it. But land is left as the ratings base for councils, rather than central government.

All of it means that it costs the country a lot more than a dollar to raise a dollar in tax. And the problem gets a lot bigger when the government wants to collect more revenue. If you’re happy with a very small government overall, tax distortions will not matter as much. But if you want the government to be able to fund a lot of things, you have to be especially careful.

New Zealand has taken a very sensible approach in trying to collect tax in the least harmful ways possible. Tax and transfers work as a system. New Zealand combines a proportionate GST with a progressive income tax and with benefits linked to family size and income.

Looking at any one part of the system on its own would be a mistake. GST is certainly less progressive than a progressive income tax. But the tax system can achieve any desired level of progressivity by adjusting income tax rates. And GST will catch consumption from types of income that are more difficult to tax – along with spending by tourists.

The system has tried, and succeeded, in taxing a broad base of income and consumption at a low rate. The combination means that the government winds up collecting a lot more revenue than it otherwise might.

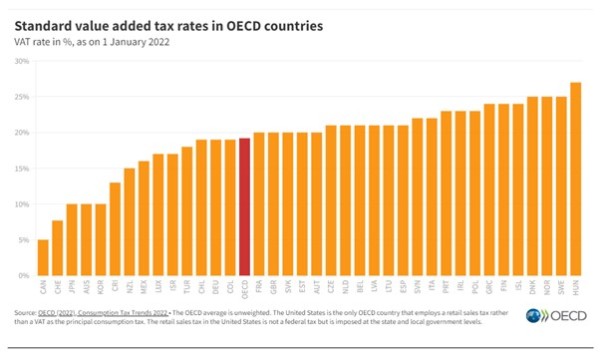

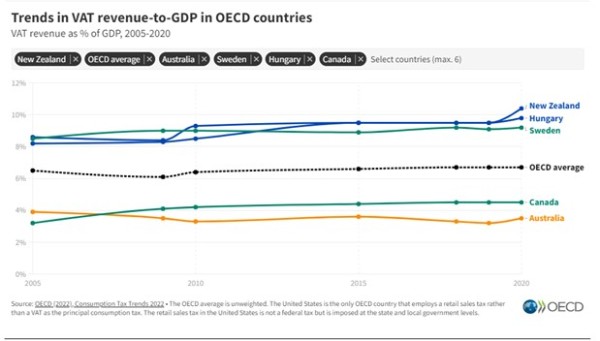

The OECD provides helpful tables.

Our GST is far lower than the OECD average. Ours is the 7th lowest. The OECD average is 19.2%. In most of Europe, Value-Added Taxes like our GST are higher than 20%.

But, on average across the OECD, VATs raise revenue equivalent to 6.7% of GDP. In New Zealand, it’s around 10%.

Why?

Other countries’ value-added taxes are full of holes.

Hungary’s VAT charges 27%: an awful lot higher than our 15% GST. But it raises about as much revenue as our GST, relative to the size of their economy.

If you’re going to have a lot of holes in GST, you need to have much higher tax rates on everything that isn’t covered by it if you want to raise the same amount of revenue. Or, you have to have much higher taxes elsewhere in the system. And every hole causes distortions: people changing their behaviour in response to the tax change. Those distortions reduce revenue.

It is true that other countries exempt food from their tax systems.

It is also true that reviews of those countries’ tax systems are scathing about these holes.

Why? If the holes were removed, government would collect more revenue at lower cost to the country. That would mean either more government spending, or lower taxes overall, or a combination of the two.

Australia’s GST is riddled with holes. The Henry Review of Australia’s tax system contrasted New Zealand’s comprehensive GST with Australia’s messy system that taxes only 57% of consumption. It noted that “A broad-based consumption tax is one of the most efficient taxes available to governments.” And especially in small open economies where investment is more mobile than consumption.

The UK’s GST is riddled with holes. The Mirrlees Review of the UK’s tax system pointed to New Zealand’s GST as a superior example. They wrote,

“New Zealand provides a working example of how it is possible to apply the standard rate of VAT to almost all goods and services. Considering just the distortion to spending patterns – ignoring the costs of complexity – simulations suggest that, if uniformity were optimal, extending VAT at 17.5% to most zero-rated and reduced-rated items would (in principle) allow the government to make each household as well off as it is now and still have around £3 billion of revenue left over.”

Even if it is the case that low-income consumers spend a greater part of their income on whatever good or service gets exempted from tax, closing those holes means you can fully compensate households while having money left over for other worthy purposes.

And reviews of our own tax system have come to the same conclusion.

Labour’s 2018 Tax Working Group showed that exempting food and drink from GST would save a Decile 1 household about $15 per week. But the policy is incredibly costly. For the same cost as exempting food and drink from GST, the government could provide a $28 weekly cash transfer to every household in the country. Or, a much higher payment to lower-income households and lower payments to higher-income households.

The Tax Working Group also warned that, based on overseas experience, only about 30% of a GST reduction works its way through to consumers.

Think Labour’s 2018 Tax Review was biased? Fine. It reaches the same substantive conclusion as work by Ball, Creedy and Ryan, published in New Zealand Economic Papers in 2016. Professor Creedy is arguably the country’s foremost expert on tax economics.

Their conclusion, after pages of math and analysis? “The analysis supports earlier studies suggesting that the use of zero-rating in an indirect tax structure provides a poor redistributive instrument compared with direct taxes and transfers.” That’s their polite way of saying that the policy is stupid. They’re more polite than I am.

If you want a more progressive tax and transfer system, creating holes in GST is a very bad way of achieving that objective.

GST is on everything. Richer households spend more money on everything. The money collected from GST goes into the pot that the government uses for spending on everything, including transfers to poorer households. Taking GST off of food means less money is available for any of those worthy projects – and the hole created is larger than any benefit received by poorer households.

Creating holes in a clean GST is stupid. The costs are much higher than any benefit received by households. Even if it were simple to create and administer exemptions, it would be a bad idea.

But it is not simple to set exemptions. Any boundary you set will invite costly litigation about whether a product is taxable or non-taxable. That makes an already stupid policy even worse.

The UK had 13 years of litigation over whether a tea cake was taxable. Whether Cornish pasties were taxable or not drew similar controversy, along with worries about a £100,000 donation from the head of pasty firm Ginsters to the Conservatives.

People invent new food products in response to these tax definitions. DuelFuel created a snack bar that tried to be a flapjack and cake/brownie combination, perhaps because those latter products are zero-rated while snack bars are not. The tax department eventually ruled it was a snack bar and taxable.

A tribunal had to decide whether ‘Mega Marshmallows’ were a taxable confectionary, or exempt. Because it was intended to be roasted over a bonfire or barbecue and then eaten, it was considered exempt. But it was appealed to the Upper Tribunal. So we still do not really know whether or not it is taxable.

Australia got itself into the same messes because coalition politics prevented a clean GST. The result? An Italian expert had to be flown in as part of litigation over whether a mini ciabatta is taxable cracker or non-taxable bread. Pizza rolls add further complication.

A 2015 review of the Australian tax system pointed to the harms. Deciding whether or not something winds up being taxable “is complex and undertaking [the analysis] places a considerable burden on businesses.”

Wherever a boundary is drawn between taxable and tax-exempt items, you’ll get litigation.

Set the boundary to exempt fruits and vegetables, and there will be fights over how much processing is allowed before it is taxable – and plenty of other boundary case decisions. Frozen vegetables? Canned? Canned in a sugar syrup? Jam? Lines will be drawn somewhere.

Set it around grocery food, and there will be fights over whether prepared sandwiches at grocery stores are taxable or not – and countless other boundary case decisions.

Set it around food full stop, and there will be fights over ingredients that can be used for food or for other purposes. Baking soda is used in some industrial processes – as an example coming quickly to mind. It will be impossible to tell in advance where the messes will be, but there will be messes.

Don’t believe me? Listen to Australia’s judges, who are stuck administering their nightmare of a system. Justice French argued Australia’s tax system causes complexity for no clear purpose. Four Federal Court judges were tied up in litigation over the mini ciabatta; the judges eventually found that it was “of the cracker genus” and consequently liable to tax.

New Zealand has maintained a clear bright line on GST. It’s something we get right that everyone else gets wrong.

Once you grant an exemption for one worthy-sounding thing, it is hard to resist the call for more. Books. Hygiene products. Health care and supplements. Gym memberships. Children’s clothing. All will draw their own costly lobbying for exemptions. The only real winners will be lobbyists, accountants, and lawyers.

If you want the tax system to be more progressive, look at the income tax schedule. If you want poorer people to be able to afford more things, increase benefits or transfers through Working for Families. And consider liberalising zoning so more housing can be built and so rents can come down. If you want groceries to be cheaper, make it less impossible for competitors to enter the New Zealand market – ease zoning and consenting and overseas investment restrictions.

Every bit of advice the government will have received on GST and food will have said that exemptions are stupid. If Labour proposes exemptions, it’s a bet that voters are stupid too. Are you?