The world’s major economies are walking into the next global financial crisis. Moreover, their authorities do not seem willing to change direction. They fear that raising interest rates or cutting government budget deficits risks precipitating the collapse they seek to avoid.

Those are the major conclusions of our report we released last Thursday.

In response to the Global Financial Crisis over a decade ago – and then again to Covid-19 – worldwide, major central banks have eased monetary policy settings to an extraordinary and potentially destabilising degree.

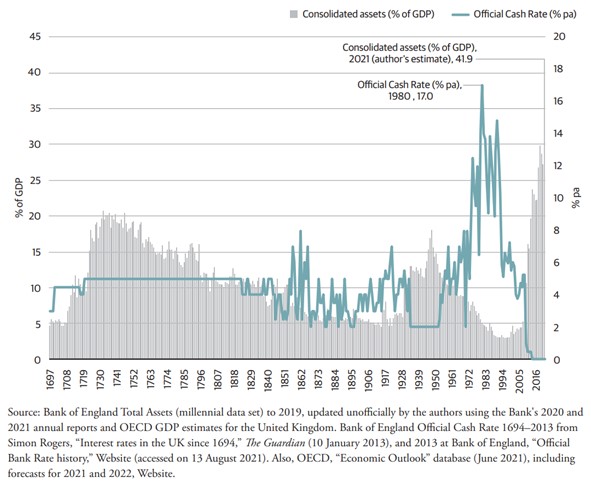

The Bank of England is the world’s oldest central bank. Never since 1697 has its control interest rate been as low as it is today (0.1% pa). Never has its balance sheet relative to gross domestic product (GDP) been as bloated from creating money as it is today. (See following figure).

The US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, and the Bank of Japan have progressively also adopted historically extreme levels for monetary policy settings.

Simultaneously, many governments have pushed their public debt ratios up to an extraordinary degree. Federal public debt held by the public was a historic high relative to GDP at the end of World War II. Congress’s Office of Management and Budget now forecasts that this high will be exceeded in 2024 – a war-time like debt in peace time. This is unprecedented, and it is because of large ongoing budget deficits. The US Federal government’s projected fiscal deficit for 2021 is an astonishing 16.7% of GDP.

In September, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned the US was heading for sovereign default if the government’s debt ceiling was not lifted. Eventually, Congress agreed to increase the limit, but this merely kicks the debt can down the road – again.

In Europe, a condition set in 1992 for monetary union was that member countries’ gross public debt ratios should not exceed 60% of GDP. According to the latest official forecasts, only 7 of 22 countries will comply in 2021. All the largest economies now exceed 60%. The debt ratios for the seven worst cases exceed 100% – for Italy it is a crippling 166%.

Italy’s high debt ratio is a serious risk to the stability of the Euro currency block. This is because its economy looks to be too large for the rest of Europe to bail out.

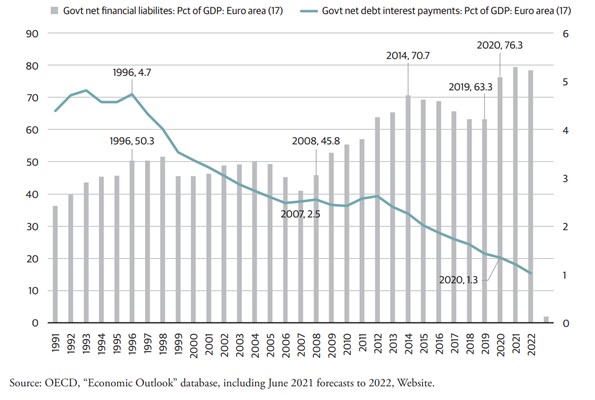

Lower interest rates invite governments to borrow more. The utter perversity of the current situation is epitomised by the fact that the Eurozone’s overall government net financial indebtedness has never been higher and the net interest cost lower relative to GDP.

China is also a potential source of instability. Serious debt problems have emerged in its housing market – which accounts for 29% of its economy. This makes it of potential global significance. The debt crisis at Evergrande – the second largest property developer illustrates the concern.

Globally, persistently low interest rates encourage firms and households to borrow excessively to buy assets that would otherwise be over-priced. That contains the seeds for that next crash.

Low interest rates also prolong the existence of “zombie” companies that should be wound up. Healthy companies could use their resources more productively.

High public debt ratios not backed by assets of comparable value give governments a conflict of interest. As economic managers, government should be leaning against excessive borrowing rather than fuelling it by low interest rates and quantitative easing.

Being heavily indebted compromises government’s willingness to act.

This problem of excessive borrowing and over-priced assets has been made worse by the signal the major central banks have been sending to investors – that the authorities will ‘do whatever it takes’ to prevent any major collapse.

Professor Arthur Grimes, former chair of the Reserve Bank’s board, wrote the foreword to the report. He succinctly identified that perverse incentive problem:

“Governments, central banks and private sector financial institutions have together created the seeds of the next crisis on the assumption that policy actions will protect borrowers and lenders from downside risks. The result has been a one-way bet for those positioned for asset price rises, while those who have acted prudently have been left behind.”

The perversity of the current situation is further illustrated by the US. In 2020, it recorded the greatest decline in economic activity (real GDP) in at least 60 years. Its unemployment rate more than doubled.

Yet US household wealth rose by a record amount (26%). In dollar terms, it rose by much more than if households had saved 100 percent of national income in 2020.

So, how could US households overall become far more prosperous amidst the biggest downturn in over 60 years? The answer is capital gains and more money in the bank because of the Federal Reserve’s credit creation and low interest rates. US sharemarkets have boomed along with property prices.

The Initiative’s report traces the path to the current government ‘debt trap’ situation, first under the gold standard and subsequently with fiat money.

There is an optimistic scenario. It requires continuing near zero interest rates; low inflation, strong growth that lifts tax revenues; and firm resolve to reduce government budget deficits.

One can hope, but each step in this scenario looks implausible. Consumer price inflation has emerged this year that can only put upwards pressure on interest rates; pressure that central banks have been resisting.

In the past, periods of excessive debt and money creation have tended to end badly. Our report considers two much less rosy, low growth, high unemployment scenarios and one disastrous one of ‘Great Depression’ dimensions.

We leave it for readers to decide what probabilities to put on these and other possible scenarios. Nor does the report speculate about the timing of the next global crisis.

New Zealanders can only take precautionary measures. Being a small and globally integrated economy, New Zealand cannot prevent the next financial crisis.

Reducing debt to prudent levels is important both for governments and households. A fiscal council could help Parliament to hold government to account for the quality of its spending.

Firms and households should avoid borrowing to excess to buy over-priced assets. A narrower and more prudent focus for the Reserve Bank is desirable.

The temptation in the face of such extremes in the major economies is to hope that somehow this global episode will not end in tears – that “this time really is different”. That is mere wishful thinking.