In the world of central banking, nothing is as sobering as being forced to confront the consequences of past policy mistakes.

Last week, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) delivered a hefty 50 basis point increase in the Official Cash Rate (OCR), raising it to 5.25%.

With other central banks around the world recently slowing their interest rate hikes, the RBNZ’s more aggressive path may look like an admirable dedication to price stability.

Unfortunately, in reality, it is the RBNZ’s desperate efforts to rectify its own blunders. In doing so, the bank is facing an uphill battle of its own making.

By its own admission, the RBNZ’s decision to raise the OCR so significantly results from its fears that inflation is not under control and the economy is overheating. And indeed, persistent inflation, a tight labour market, and continued strong economic activity have combined to create an environment in which demand continues to outpace supply capacity.

The root cause of all this is the RBNZ’s past monetary policy.

Over the Covid-19 pandemic, aside from the US Federal Reserve, New Zealand’s central bank provided the most generous stimulus per capita in the world.

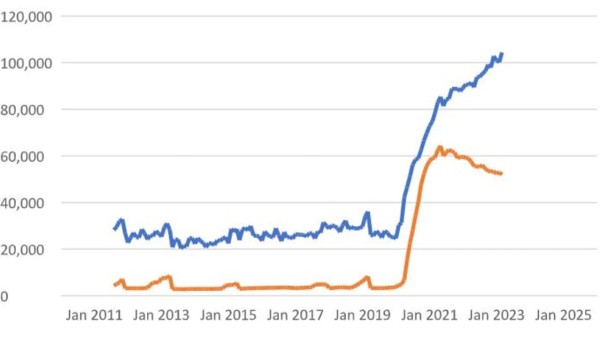

Where the RBNZ’s balance sheet used to hover at around NZ$25 billion in the decade before Covid, from the second quarter of 2020, it soared to unprecedented heights. By March 2021, it had reached NZ$83 billion. The increase from the prior baseline was several times larger than during the Global Financial Crisis.

Figure 1: RBNZ’s balance sheet size and government securities held by the RBNZ

After the initial phase of the pandemic, the RBNZ should have recognised that Covid was an exogenous supply shock, i.e. an unpredictable event that occurred outside the country but with a dramatic effect on the domestic economy. The pandemic disrupted whole industries, especially tourism and export education, and no amount of stimulus could have revived them.

Monetary stimulus was not just the wrong tool to use. It was counterproductive – it bolstered demand when supply had no way of accommodating it.

The RBNZ kept treating the crisis as a run-of-the-mill Keynesian-style recession characterised by a lack of aggregate demand. And so New Zealand’s central bank kept pumping more money into the economy – even as Covid was subsiding and the true nature of the economic shock became clear.

In February this year, the latest point for which the RBNZ provides balance sheet data, its total assets had reached a record NZ$104 billion.

Initially, many observers hailed the RBNZ’s intervention as a success as it (allegedly) helped to support businesses and households during the crisis. However, even if that were true initially, the RBNZ was too slow to withdraw its earlier stimulus.

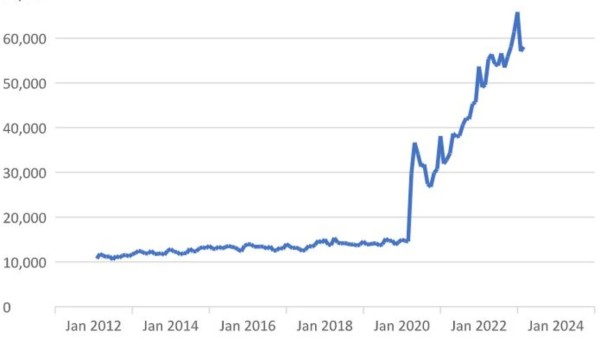

Figure 2: RBNZ’s monetary base (million NZ$)

In June last year, former RBNZ chief economist John McDermott warned that the RBNZ’s tardiness in withdrawing its stimulus measures would have long-lasting consequences for the economy and price stability. McDermott argued that the central bank’s monetary expansion was causing inflation and making mortgage rates lower than they would otherwise be. His warning has proven prophetic.

McDermott argued that all other things being equal, New Zealand’s fourfold expansion in the monetary base from pre-crisis levels would take 14 years of 10% inflation to filter through the economy. The only way to avoid such persistent price increases would be to quickly shrink the monetary base and the RBNZ’s balance sheet.

Yet, what we are witnessing is the opposite. Since the beginning of Covid in early 2020, both the monetary base and the RBNZ’s balance sheet have skyrocketed with no sign of a turnaround, apart from the RBNZ’s recent sales of some of its holdings of government bonds. Bizarrely, the size of the RBNZ’s has never been larger than it is today, despite the bank trying to take the heat out of the economy.

So, the massive monetary stimulus of the past several years remains in place – despite all the RBNZ’s increases in the OCR and despite all its rhetoric. And this stimulus continues to affect economic activity in New Zealand.

According to GDPLive.net, an artificial intelligence tool that calculates real-time rates of inflation and GDP growth for New Zealand, inflation is still running above 7%, while annual GDP growth stands at 3.4%. There are no signs of a recession in GDPLive’s data, even though the RBNZ has stated it wants to manufacture a recession to break the inflationary spiral.

GDPLive also calculates where the OCR should be if the RBNZ followed the Taylor Rule. Using this Rule, central banks can set interest rates based on inflation and economic output to achieve a target range of inflation. For New Zealand, the Taylor Rule suggests the OCR would need to climb to 9.4% to bring consumer price inflation back to a level of 2%.

By contrast, even after the latest increase, the OCR remains more than 4 percentage points shy of this (eye-watering) level. We should thus not expect consumer price inflation to return to its target range anytime soon.

New Zealanders should prepare themselves for many years of economic turbulence. High inflation, elevated interest rates, and the potential for a severe recession down the track could well be the consequences of the RBNZ’s past policy mistakes.

Ultimately, the measures needed to correct those mistakes will be a painful but necessary process for the New Zealand economy.

But it also serves as a stark reminder of the importance of sound monetary policy and the consequences that can arise when a central bank makes mistakes in its economic analysis.